Inside the June 2025 Issue

John Jeremiah Sullivan on Mark Twain, Karl Ove Knausgaard on finding mystery in the digital age, Harmony Holiday on James Baldwin, fiction from Sidik Fofana, and more.

Harper’s Magazine marks its 175th anniversary with an expanded June issue. The issue features a special symposium “Distant Mirrors” that includes original essays examining transformative historical figures from the magazine’s history, including essays by John Jeremiah Sullivan on Mark Twain and Harmony Holiday on James Baldwin. Alongside these contemporary analyses are seven selections from our archive—from Noah Brooks’s 1865 reminiscence of Abraham Lincoln to Don DeLillo’s reflection on September 11. Alongside the symposium, the issue features Jonathon Sturgeon’s letter on the Kentuckiana killings, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s essay on finding mystery in the digital age, and Amanda Chicago Lewis’s report on the United Nations’ aspirations and shortfalls.

—Christopher Carroll, editor

[Symposium]

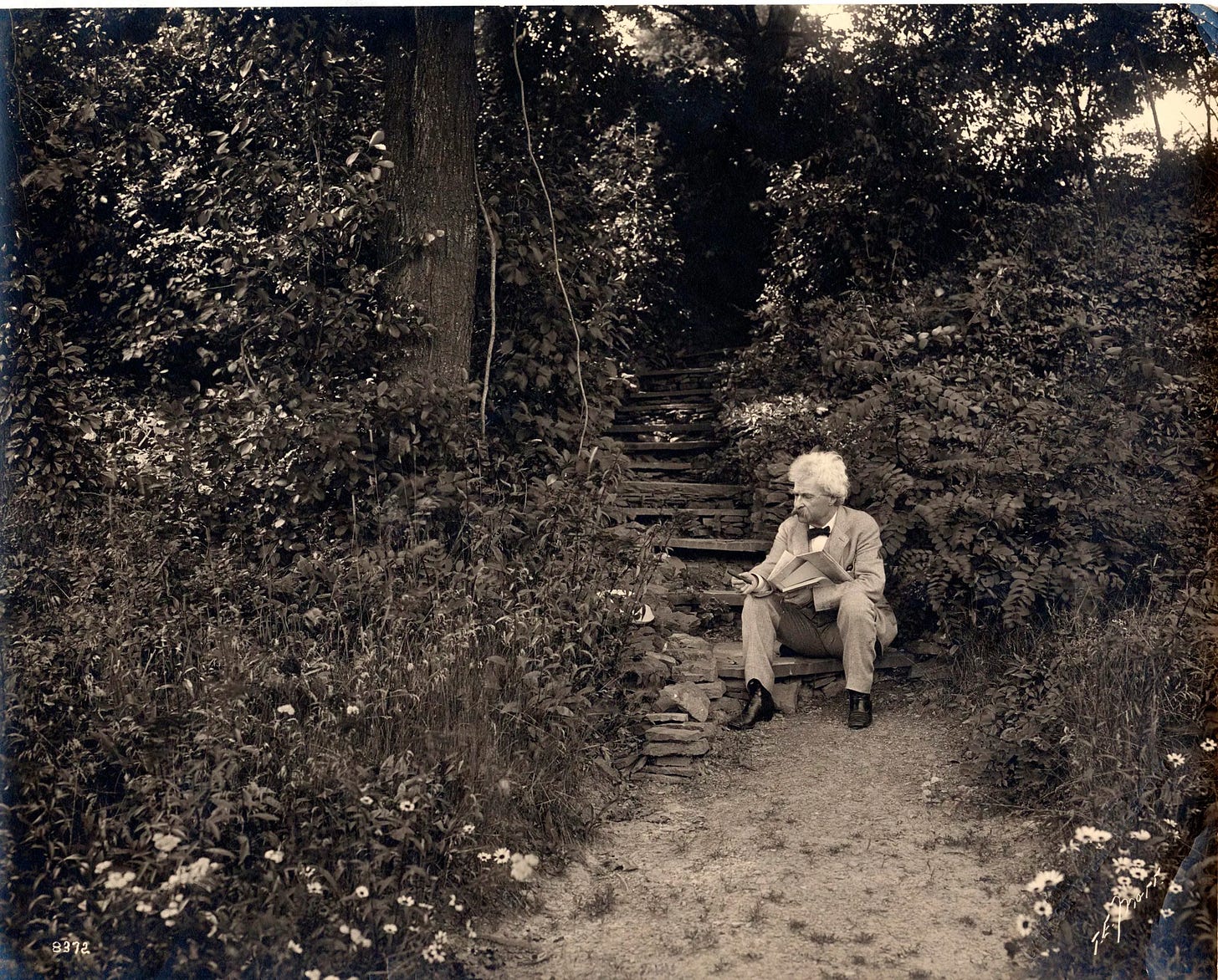

Twain Dreams

The enigma of Samuel Clemens

I grew up so hopelessly steeped in the cult of Twain that I have to perform a mental adjustment to understand how a Twain revival could be possible. How does one revive what is ever-present and oppressively urgent? My sportswriter father, who died when I was in my mid-twenties, worshipped Twain, to the extent of wearing, every year on specific occasions, a tailored white suit. With the shaggy hair and Twainish mustache that he maintained year-round, the object of the homage was unmistakable. I was raised in New Albany, Indiana, across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky, and in the late Seventies, when I was a boy, some of the last of the old-time steamboat races were held there. One of my earliest memories is of being taken down to the riverfront at the age of four to watch that spectacle. Twain’s face was everywhere. It was on TV, in a disturbing Claymation film called The Adventures of Mark Twain, which, I have since learned from the internet, gave bad dreams not just to me but to my whole microgeneration. Every Christmas until I was a teenager, I would find waiting under the tree a fine hardback copy of one or another Twain novel, sometimes one of the editions that had those marvelous N. C. Wyeth illustrations. These gifts would then stress me out for the rest of the year. They were given in love, but with a certain expectation or pressure, as well—they were a form of cultural proselytizing—and somehow I never felt that I read or loved them well enough. My father would quiz me on the stories. Hadn’t I loved the part when such and such happened? When Huck decided he’d rather go to hell than hand over Jim to be reenslaved? No, more than that, more than any “rather,” did I grasp the fact that Huck actually believed he would go to hell for this loyalty to Jim, and chose it regardless?

[Essay]

The Reenchanted World

On finding mystery in the digital age

Translated from the Norwegian by Olivia Lasky and Damion Searls

The first time I saw a computer was in 1984. I was fifteen years old and living in a sparsely populated area near a river, miles away from the closest town, in a far-northern country at the very edge of the world. A sign lit up above the convenience store that closed at four o’clock every day; otherwise, the visual stimuli were limited to fields and trees, trees and fields, and to the cars driving along the roads. In autumn and spring it rained so much that the river overflowed its banks—I remember standing in front of the living-room window watching the water cover the field where we played football, the goalposts rising up from it. There was one TV channel, two radio stations, and the newspapers were printed in black and white. The news from Iran and Israel, Egypt and South Africa, England and Northern Ireland, the United States and India, Lebanon and the Soviet Union all took place far away, as if on another planet.

To understand a man, you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty, Napoleon is supposed to have said. The quotation is probably apocryphal, but that doesn’t mean it’s not true. For me, it is this world by the river that counts. When I sit down to write a novel, the natural time for it to take place in is the Eighties, as though that era embodied the world’s true form, its essence, and everything that came later were a kind of deviation. Even though I google various topics as I’m writing, the characters in the novel don’t google anything; it never occurs to them. The same is true when I dream. Cell phones and the internet never appear in my dreams, which are populated mostly by the people I was surrounded by forty years ago.

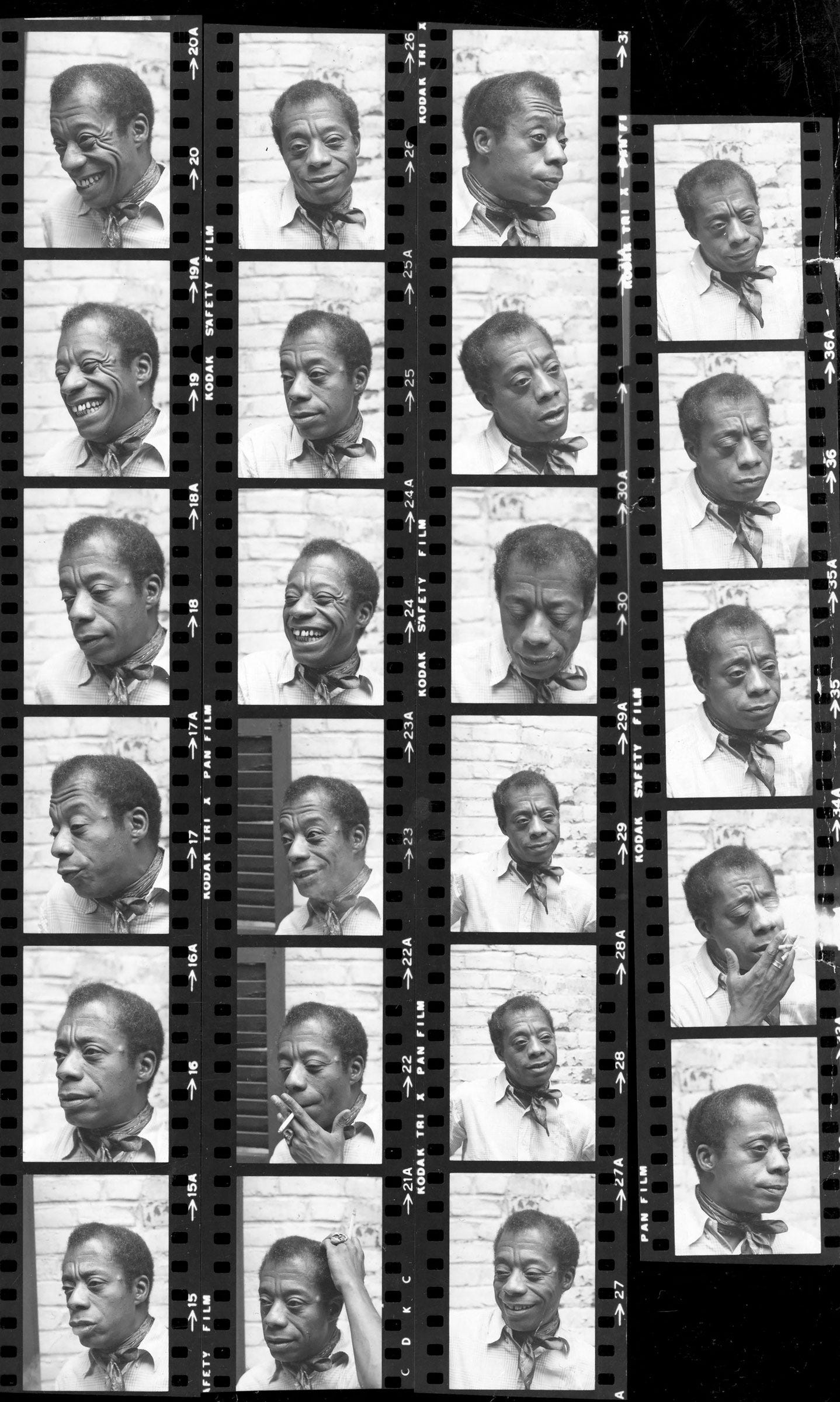

[Symposium]

For Those Who Would Be Real

James Baldwin’s testimony in images

I’m scrolling through terrible images on the internet the way James Baldwin describes browsing on a television some mornings before getting out of bed, switching from channel to channel restlessly, then deliberately, so that the slurring between pictures unfolds as its own story in defiance of the programs from which each now-stray image derives, when I realize why I’ve been hesitating to write just another elegy for the effigy of James Baldwin at one hundred or one hundred and one. It’s been redundant and incessant, our fetishizing of this man and his thinking, the fashioning of an idol out of someone who was inherently suspicious of worship, and it’s caused his ideas to ossify and lose their visceral impact, deracinated now, the way commercial jingles made of soul songs betray that music. You can never dance to it or with it again, and we can never again enjoy James Baldwin outside projections of his gravitas. He has been hijacked that way and gutted for parts, and all of us have contributed to turning him into one of the monsters of innocence we yearn to become, an unassailable symbol. We’ve diluted James Baldwin’s person and used him up the way we do the black people we discover in our folkloric GIFs and memes, black people whose gestures we turn abstract and viral overnight, and replay for weeks or even years, then discard once the inside joke has expired.

[Letter from Louisville]

Sons of Good Fathers

On some killings in Kentucky

We both, in our early twenties, had nervous breakdowns in Louisville after graduating from college. Connor had known nothing but success in his young life, racing through his undergraduate studies and a master’s degree in finance at the University of Alabama in four years, before starting at the bank. That is when he became depressed. My own melancholia dissolved after a spell as a janitor at the Highlands Latin School, where Wendell Berry taught Shakespeare to students while I cleaned. Connor’s mania ended when he murdered five colleagues at Old National Bank on April 10, 2023, and was himself shot to death by an officer of the Louisville Metro Police Department.

The official reason given for Connor’s murders, if we are to believe the Washington Post, is nepotism. There is a truth to this, I can confirm. The grieving survivors of this second Sturgeon massacre told the Post that Connor’s nepotistic rise at the bank led to his first failures as a man, that he responded as young American men do, with wounded pride, an AR-15 rifle, and 120 rounds of ammunition. Connor told the story a bit differently. He wrote that he aimed to kill rich white Americans to prove that a sick person could too easily get an assault weapon and kill rich white Americans. But I don’t think guns were his reason; they were his justification and method. And nepotism was but the half of it. The other half was nepotism, by which I mean property.

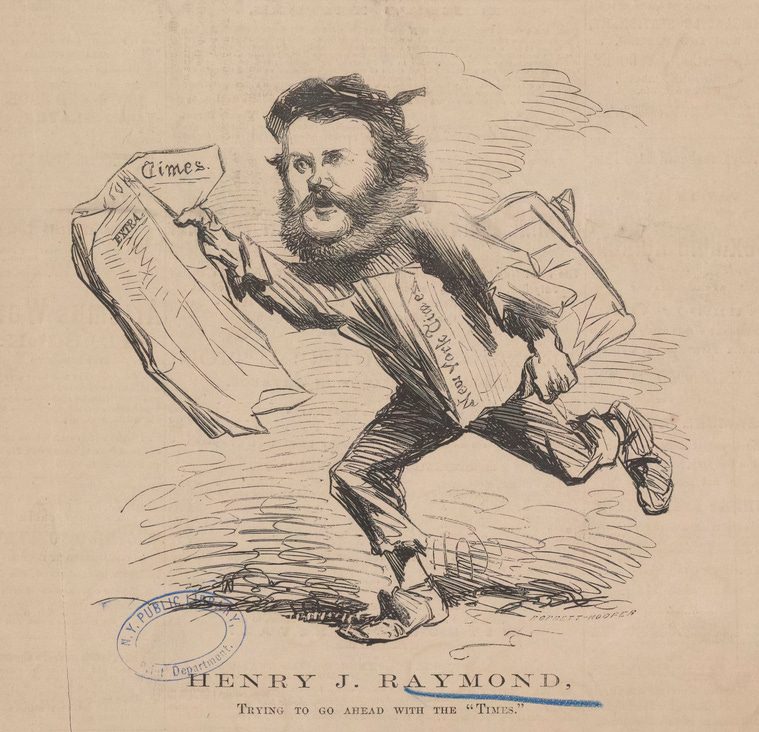

[Symposium]

The Mild Revolutionary

On Henry Jarvis Raymond

By Matthew Karp

Across an eventful life in journalism—which included the management of Harper’s in its infancy—Raymond managed to occupy the political center with the firmness of magnetized iron. Yet the striking fact about the American Civil War era, and the chief paradox and fascination of Raymond’s own career, is that the political center kept moving.

[Report]

Wishful Thinking

The aspirations and failures of the United Nations

I was curious about why the United Nations had come to seem so irrelevant. At a moment of global instability and rising nationalism, I wanted to know what had happened to the grand institution we had created the last time the world sank into a violent cataclysm, to make sure Hiroshima and Auschwitz and Stalingrad never happened again.

[Story]

Tom Robinson

By Sidik Fofana

Bustin it up inside don’t make it easier to carry out the pieces—well, it make it easier, but you want all that bangin inside and it’s hot?—you carry it outside so the noise and all that jazz don’t get to you. Jesus, Cooter, will you just listen to me? Bottom line, bottom line is, this girl invited me in the house, inside. And you know me, I always like seein where shit will go.

[Archive]

From the Archive: 1850-2025

Selections from our archive, including Noah Brooks’s 1865 recollection of Abraham Lincoln, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s 1938 poem on the Spanish Civil War, Edward W. Said’s 1992 essay on returning to Palestine, and Don DeLillo’s reflection on 9/11.

Order the June issue at store.harpers.org